<B>Hawthorne's Arkansas Infantry</b>

Prisoner of the Yankees!

At Fort Deleware near Deleware City, Deleware

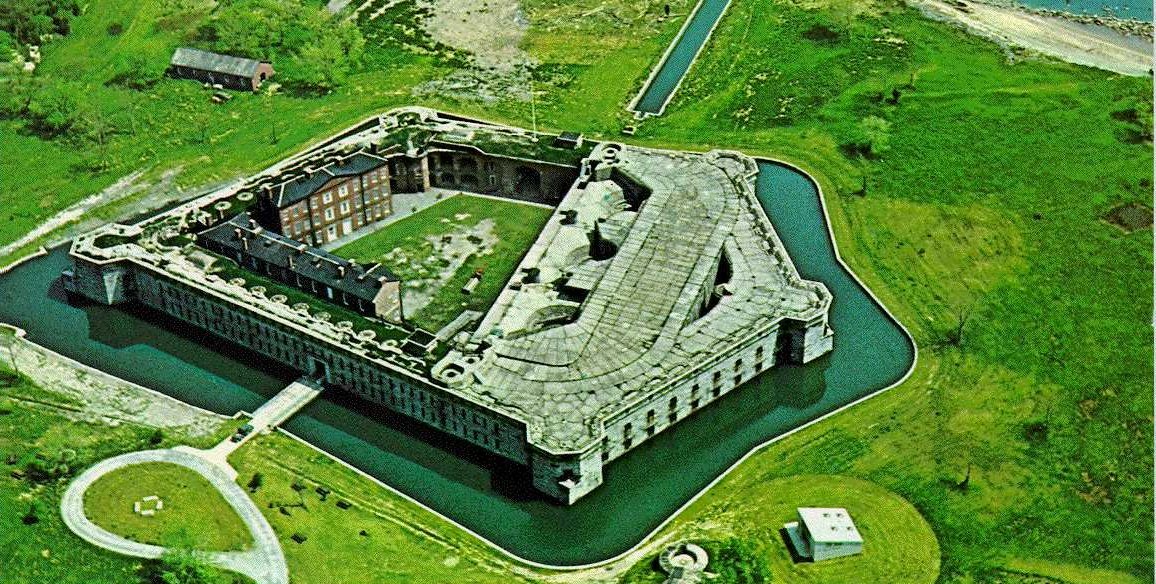

Aerial Photo of the Fort Deleware, Deleware Civil War Prison.

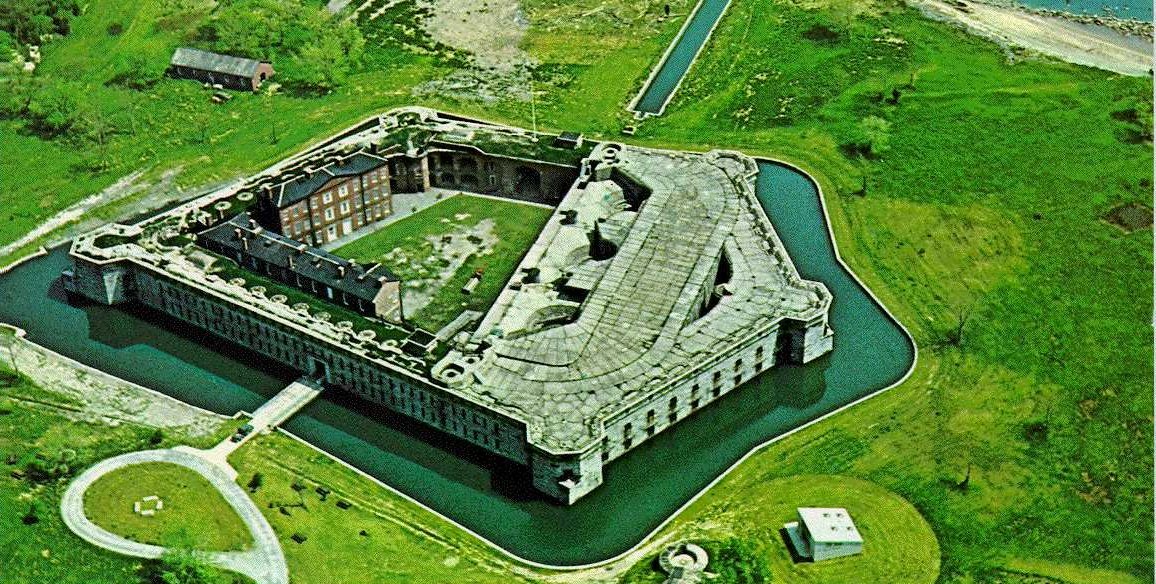

Aerial Photo of the Fort Deleware, Deleware Civil War Prison.

The prisoner shacks or barracks was outside the wall in the low area.

NOTE: The following letter was written by Lt. THOMAS who was also captured by the Yankees and spent the duration of the war in the same prison camps as my great-grandfather and oddly enough, at the same time. The only difference, Lt. Thomas was captured in October, 1863 in northern Mississippi and my great-grandfather was captured at Helena, Arkansas July 4, 1863. This article was taken from a Houston Texas newspaper, Sunday magazine section The Star in 1977.

PRISONER OF THE YANKEES

Mrs. Shiplet, a widowed mother of seven children and grandmother of two, edited a journal her great, great uncle, DeWitt Clinton Thomas, wrote for future members of his family about his experiences in a Yankee prisoner of war camp.

The story has everything - tragedy, joy, love, hate, kindness and cruelty.

D.C. Tthomas happened to be a rebel soldier, but he could just as easily have been a Yankee. Most important for the nation, Thomas emerged from his ordeal a whole man, still capable of love and caring and getting on with the healing of the nation's wounds. Today, 112 years later, that task is almost complete.

Thomas was a 2nd Lieutenant of Company A, Texas Mounted Rifles. In October, 1863, while scouting near the Yalobusha River in northern Mississippi, Thomas was surprised and captured by a Yankee Patrol. He was taken to Memphis, Tenn., where our story begins:

**************************

Every day the ladies of Memphis would drive by the front of our prison and kiss their hands to us or throw flowers to us. The ladies were true Southerners, as kind and hospitable as women could be.

We remained in Memphis some 10 or 12 days. Our names were taken down and a roll made up. finally, we were marched through the city, down to the Mississippi River, and ordered on board a filthy old steamboat.

In a short time, we were going up the great Mississippi. About dusk, someone shouted: "The yawl is gone!" In an instant, a hundred Yankee soldiers were at the hurricane deck, guns in hand.

I looked out far down the river and could plainly see the little boat. No one seemed to be in it, but in a minute more, it was out of long-range gunshot, and we saw three men raise up in the yawl, put out paddles, and strike for the Kansas (sic) shore.

We rejoiced at the success of our companions in arms, especially since one of them had been captured just a few days after his marriage. Now he was landing within a short distance of his wife.

We watched the boys land safely and walk up the bank. In another moment they were out of sight.

Nothing else of notice transpired until we reached Alton, Ill. Here we were landed and marched to the old penitentiary building with as little ceremony as if we were a herd of swine.

I looked up to the iron-grated windows and recognized several faces, among others, that of Dr. J.S. Riley. The doctor and myself had been politically opposed to each other in Texas and were not on very good terms, but by signs and motions he made me to understand that we would be searched. A small slip of paper fell near me on which was written: "Hide your money, boys."

This card was passed rapidly from one to another, and we were a busy crowd. I enquired of the guard if he would permit me to speak to a friend. He gruffly answered: "No!" But at the same time he turned his back and looked the other way.

I sprang to the gate and shook hands with the doctor, taking care to leave my five-dollar gold piece in his hand. After I learned them better, I would not have risked as much for a room full of gold. The guard could easily have shot me dead, and would no doubt been justified by his officers.

They took from me my matches, my tin cup, my buttons and the like, but fortunately failed to find the money I had sewed into my clothes while waiting to be searched. They also let me keep my boots.

I was hurried out through the inner wall of the old penitentiary and I found myself among about 1,200 rebel prisoners.

Our situation was calculated to depress our spirits, but feeling that our cause was just, we tried to be cheerful. When night would come, we would collect in groups and sing aloud the soul-stirring songs of Dixie, thereby casting defiance in the teeth of our enemy.

The winter was unusually severe, even for that climate. We suffered from cold day and night. The ground was covered with snow and our facilities for fire were poor, and coal or wood was not very bountiful.

Christmas came, and we could hear the merry-making from outside the walls of our prison, which of course reminded us of better and happier days. New year's morning, 1864, was, I think, the coldest day I ever experienced.

The wagon on which water was brought from the Mississippi River, would come into the prison enclosure with icicles hanging to the ground as large as a man's arm. Water thrown up would freeze before hitting the ground. When we awoke, our boots would be frozen and difficult to get on our feet.

Twenty of us joined together and rented a small room in the penitentiary and repaired the roof. Although it joined the "dead house," it was better than sleeping in the convict cells of the filthy old penitentiary. We also bought a cheap stove and did our own cooking. Some of our friends could correspond and get money, and they liberally spent it for the benefit of all.

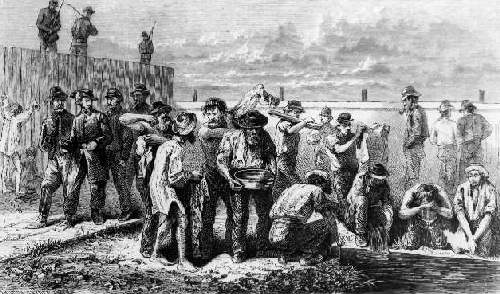

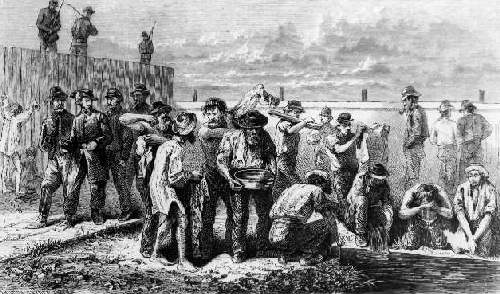

Wash Day at Fort Deleware!

Wash Day at Fort Deleware!

About this time, smallpox broke out in the prison and patients, as fast as they were attacked, were carried to a "smallpox island" in the Mississippi River - a sandbar with a few willows growing on it.

Sometime in January I was stricken with a burning fever. Dr. Riley pronounced it a case of smallpox, one of the most unpleasant announcements I have ever heard.

It was necessary for him to report the case, and I began to prepare to cross over to "The Island." I gave my little effects to my friend, BOB ROBINSON, with instructions in case I should not recover. In company with several others, I was drawn on a sled across the ice to the smallpox island. The first words I heard were: "So you have brought some more dead men over here for us to bury." I inquired for Dr. Gray, as Dr. Riley had told me to do.

Dr. Gray instructed one of the nurses to provide a place for me to lie down and before long I found myself on a bunk, one or two blankets under me, one or two over me, with a stick of wood for a pillow.

Dr. Gray, a rebel soldier of Mississippi, proved to be quite a gentleman. He visited and encouraged me but frankly told me that his supply of medicine was limited to a little Epsom Salts and quinine. At night I had a severe chill and next morning I had almost given up in despair.

A nurse came round and enquired how many blankets I had, and being informed that I was in possession of six, said that was more than I was entitled to. I explained that two of them were my own private property, that I had brought them with me. With an oath he took two of the blankets off of me, and walked off with them.

A convalescent, P.S. Lane, had seen and heard all that occurred between us, and after the nurse left, came to me, spoke kindly to me, and told me to be patient, that as soon as night came, he would find me plenty of cover.

True to his promise, that night friend Lane came to me with a pair of heavy blankets, tucked them round me and left me in a measure comfortable, promising to come back in the morning. He did come, and the noble hearted man took off my filthy socks, washed them out clean, and waited on me like a brother. Again, I had found a friend in the hour of need.

I cannot describe my own suffering, which seemed at times more than I could endure. But many suffered more severely than myself, and they were dying around me nearly every day and night.

After some 25 days, about 15 of us were pronounced sufficiently recovered to return to prison. We were ordered to dress and take up the line of march across the river.

The sun had shone for several days, and the ice on the river had begun to thaw, so that we literally waded through soft ice to the prison, a distance of about a mile.

When I arrived at my old mess, and met my old friends all well and hearty, I was as happy as a man could be under the circumstances. My friends prepared me a warm supper, and that night I lay down beside my old friend, BOB ROBINSON.

The next morning I awoke stiff and sore, thirsty and feverish, with no appetite, and feeling very unwell. Dr. Riley came to my relief, but the wade across the river was too much for me, and soon I was seriously ill again. We kept this concealed from the Yankees, for I did not want to go back to the hospital.

The little room we had rented stood about 40 feet from the wall of the prison. While I was on the island, the boys had agreed to a plan of escape and had drawn up articles of agreement and had signed and sworn to them.

They had contrived to get possession of a large pocket knife, and with it they were tunneling under the wall.

They had a small box with a string attached, and when one man had filled the box, another at the entrance of the hole would withdraw it and a third would conceal the dirt under the floor, in our bunks - anywhere.

The work had to be done at night. They had organized a system and it went quite well.

One night during our mining operations, the door of our room was burst open and the rays of a lantern shot upon us.

Everyone was ordered outside. Robinson, a noble fellow, simply remarked: "One of our men is sick and cannot walk. He has nothing to do with it."

The colonel, who carried the lantern, walked down to where I was lying and cursed me soundly for not informing on my companions. Then he threatened to tie me up and throw me in the Mississippi River. My companions were led away and I was left alone.

I continued to get worse, but Dr. Riley attended me closely. Later, he succeeded in having my friends released from their close confinement and one-by-one they came in, spoke to me, gazed on me for a few moments and went off.

I was not blind to what was happening. The boys had gained admission to see me before I died. I thought of the terrible dead house, of the old gray horse cart that was almost daily carrying off some of the prisoners to the graveyard.

I thought of the cold, cold grave in this cold, unfriendly climate, far away from the sunny South. I thought of my distant home, of parents, brothers, sisters and friends now far away.

I fought to live. Dr. Riley administered a stimulant and I rallied in a few hours. The great change in his face told me that I was pulling through the worst. I rested and slept a little. Then my excruciating pain gave away and sweet sleep followed.

About two weeks later I was permitted to return to my old companions. From them I learned that a roll was being made up of the prisoners who could be moved.

Although I was very feeble, I was determined to make the trip and stay with my friends. We were examined by a board of surgeons before being added to the list of those being moved.

I could only walk with the help of a stick, so we had to resort to a ruse. When it came time for my examination, I placed a hand on the shoulder of a friend of mine on either side of me and carelessly approached the door.

There I steadied myself, than made a bee-line to the place where the surgeons were sitting in judgement. They asked me if I had smallpox, looked at my tongue, and after a few more questions, put my name on the list.

We were moved by train and ship through Illinois, through Terre Haute, through Indianapolis, through Pittsburgh, through Valley Forge, across the Allegheny Mountains.

After five days we reached Philadelphia and were ordered aboard a steamer. The next morning the steamer landed at Fort Delaware, on Delaware Island in Delaware Bay, 45 miles below Philadelphia.

The fort, a huge stone structure, is built near the south end of the island. On the northern end, barracks had been erected for prisoners.

The barracks were built of plank and called "box houses." the outside walls of the barracks formed a square. Each barrack was divided into divisions, each division being 32 rooms capable of holding 500 men or more.

Bunks were arranged along the entire length of each building in three tiers, one above the other.

After dark, the first night of my stay, I could hear the pat-pat-pat of many feet around me. I had no idea what it meant, but a few days later I not only learned what it meant, but found myself engaged in the same business.

Our plan for sleeping and not freezing was for part of us to have all the blankets while the others would keep warm by violent exercise. After one group would become exhausted, they would arouse the others, take charge of the blankets, and the ones just aroused would start trotting to keep from freezing.

Each morning we filed into the "dining room," where there were tables with small piles of bread and meat laid out for each man. Each man would grab his ration and go outside into the back yard.

Then there would be frantic trading. Bread was traded for meat, food for tobacco, and so forth. We would stay outside in the cold and mud for several hours until there was a signal to go back to barracks. Then there would be a stampede for the barracks, because the first men in would be most likely to get next to the stove for a few moments to warm their hands and feet. Then they would be crowded away by the pressure of others coming inside.

I was still weak and feeble and any effort on my part to get to the stove was folly. I went straight to my bunk, took off my wet boots and sat with my feet under me. I could watch the terrible wrestles of those trying to get near the little stove.

We were seldom allowed to remain inside in peace very long. Soon there would be the cry, "Hack out," and each man grabbed his blanket - if he had one - and ran out the door.

The first time this happened I asked a man about this and he took time to say, "It is a general search. If you have more than one blanket, hide it the best way you can and be in a hurry about it."

Outside, we were searched and the Yankee robbers took blankets, coats, knives, tin cups and such other things as they could use or sell, either to someone else or back to us.

Once, twice or thrice a week we had a hack out, until they finally become satisfied we were no longer worth robbing and they devised other means of punishment.

I was a great smoker, and soon after our arrival at Fort Delaware, my tobacco and money was exhausted, so I had to do without my smoke for awhile. I had observed an old talkative fellow who kept his pipe hot, and seemed to be well supplied with the week. I did not know his name, but he had a generous face, and I went to him and asked for a pipe of tobacco.

Without hesitation he turned and pointed to his bunk, saying: "Go up there and tell my partner to give you my tobacco sack". I went up, filling my pipe and felt so good and cheerful that I commenced a conversation with the young man in the upper bunk. I learned that he was from Bell County and that his name was Jackson. We had been neighbors in our youth, but had been separated for many years.

When the old man came up, Jackson introduced us and the result was an invitation to smoke with them until I could obtain tobacco myself. I did not know when or where my next tobacco was to come from, but it did come, and often when his supply was exhausted. I had the solid satisfaction of seeing the old man sit on my bunk and make the blue smoke curl from my tobacco.

The winter of 1864-1865 passed away and spring came. Each barracks had a foreman whose duty was to see that the sick were carried out to the hospital, to count their men to the table, to call the roll and to receive and distribute the mail.

His most important duty was to draw their money and convert it into sutters checks and distribute them.

Reenactment outside the old prison walls!

Reenactment outside the old prison walls!

We were not permitted to have the money sent us by our friends from the outside, but after it had been very liberally discounted, we received sutters checks, small bits of parchment with figures of 5, 10, 25, 50, or 100 printed on them. One day to my surprise I was informed that the boys had obtained permission from the Yankees to have an election for a chief foreman and I was solicited to become a candidate for this position.

This was only a little thing, but I really liked the present incumbent, and declined the honor. I left the barracks. On my return, I found that the election was over, and that I had been chosen by a large majority as chief of the Texas Barracks. I consented to serve.

The position gave me many advantages, but was in some respect unpleasant. It became necessary for me to court favor with the Yankees so I could be of more service to the division.

This position gave me the undisputed right to remain inside the barracks in time of a hack out and to retain my baggage and blankets free from search. I was also permitted to loiter round the dining tables during the entire time my Division was passing through, and often drew double rations.

Time rolled on and summer came. The fresh water for the use of the prison was brought by steamer from the Brandywine River.

For some cause, I never knew why, our fresh water supply was cut off, and we were likely to perish of thirst.

One day, passing through the crowd, I heard my name called, and looking around saw the good-natured face of my friend from the smallpox island, LANE.

He slipped a cup of water from under his coat, which I eagerly drank and passed on. I think this was the only cup of water that I had tasted for near a week. Oh, how sweet it tasted. If Lane had never done anything else for me, I should have never forgotten him for this one kind deed. He did it at the risk of being punished and removed as cook from the officer's cook room.

Days and months passed by and the Confederate prisoners were now an army of living skeletons, starving to death. Summer was now on us, and we needed but little in the way of clothing. But winter soon came, and we were compelled to go through the same ordeal.

Spring appeared again. The shore on each side of us, Delaware on one side and New Jersey on the other, was clothed in living green. We could gaze out and behold the beauties of nature, but could not enjoy them.

I often thought that if I were only back in Texas and had enough to eat I would be supremely happy.

One day everything in and about the Fort seemed to be in commotion, and soon learned that Abe Lincoln had been assassinated by Booth.

The Yankees were like wild men, and abused the prisoners without mercy. The sick were driven from the hospital to the barracks, the guard was doubled over us. The guns of the fort were turned around so they pointed at us and we could be annihilated in a few moments.

We were informed that the guards had orders to shoot down any man who was seen to laugh, and if more than three men were seen grouped together to fire in among them.

All communication was cut off from the outside world and our mail all held back from us. We could only lie still in barracks, and wait for the result.

It was perhaps a week or ten days before the great guns of the fort were swing around and once more we were permitted to have our letters.

Again all was commotion about the fort, but this time the faces of the Yankees were lit up with a smile. The guns at the fort opened their mouths and belched forth flame and thunder until the whole island trembled. Too soon I heard the very unwelcome news: "Lee Has Surrendered."

Later we found out that Lee had surrendered several days before Lincoln was assassinated and now the rest of the Confederate generals were also surrendering. The war was over and the South was beaten, even if the North's president was dead.

Our minds were filled with terrible thoughts, and we were kept in a state of suspense for several weeks.

Finally the mandate was read, and to all who would take the oath of allegiance to the United States, the promise of a speedy release was made. The Texas prisoners gathered around and inquired what to do. I had but little to say and did not know what was best.

But I told them that as we had no army or government, no country or home, that when the time came, I would swallow the bitter pill, and take the oath. They talked the matter over and we all agreed to take the oath.

We had done all that men could do. We had faced death for four years, and now after all of our suffering, we were conquered and subjected to all the indignities they might see fit to heap upon us.

When the morning came for us to take our leave of Delaware Island, Texas Barracks was out in a body, except one man. Frank Welch was sick at the hospital, and unable to travel or leave his bunk. I went to see him and the poor fellow's eyes filled with tears, but I tried to encourage him by telling him that I hoped he would soon be able to join us.

I had two dollars - green backs - and gave him one of them, grasped his hand and soon was on board the steamboat. I wrote to Frank after I reached Texas, and his brother replied that he never reached home. He died where I had left him.

In many ways Frank was a symbol of what happened to us - a good man, who fought for a cause he believed in and gave his all. He and many others like him will be sorely missed by all of us who survived this terrible ordeal.

Thomas returned to Texas to find his parents dead and the family home is disrepair. He began to rebuild. He ran for judge in Lampasas, Texas, and was elected several times. In 1878 he began writing the journal of his life from which the story above has been taken. Thomas died in 1917, at age 82.

Copyright ©"The Star", a Magazine Section of The Houston Chronicle, Houston, Texas, July 5, 1977

Go to History of Hawthorne's Arkansas Infantry Homepage

Go to History of Hawthorne's Arkansas Infantry Page 1

Go to History of Hawthorne's Arkansas Infantry Page 2

Go to History of Hawthorne's Arkansas Infantry Page 3

Go to History of Hawthorne's Arkansas Infantry Page 4

Go to History of Hawthorne's Arkansas Infantry Page 5

Go to Civil War Records of Corpl. Jeptha Daniel Armstrong

You may send us e-mail: